When I was little, hundreds of blue, syrupy plums dropping to the ground in my grandparent’s yard told us summer was over. In the heat, the smell was so intense, so sweet, it silenced the blue hydrangeas and the dust overturned in the driveway. Tomorrow, I could get dropped in the middle of nowhere, blindfolded, and name the smell and sound of plums falling.

Last week, I picked a box of plums and mentioned to my grandmother how their smell alone reinforces such a significant portion of my childhood. She’s 94, and now so often agrees to memories presented to her, almost contractually, before she has truly remembered or processed her place within them. When I mentioned the plum smell, and the tree that used to sit in the corner of her yard next to the blue abelia, her eyes drifted up and away from mine. For her, the act of considering the memories associated with that tree was physical—the act of recalling that tree was a matter of recalling a woman who raised five children beside it, a woman who turned a blind eye the summer the neighborhood kids stole from its branches, and threatened divorce when my grandfather, his brain no longer his own, picked every last plum a month too soon. The act of remembering that tree meant remembering that when that same woman, a week later, asked him to pay attention to the pears, she was saying she was sorry and that she loved him all at once.

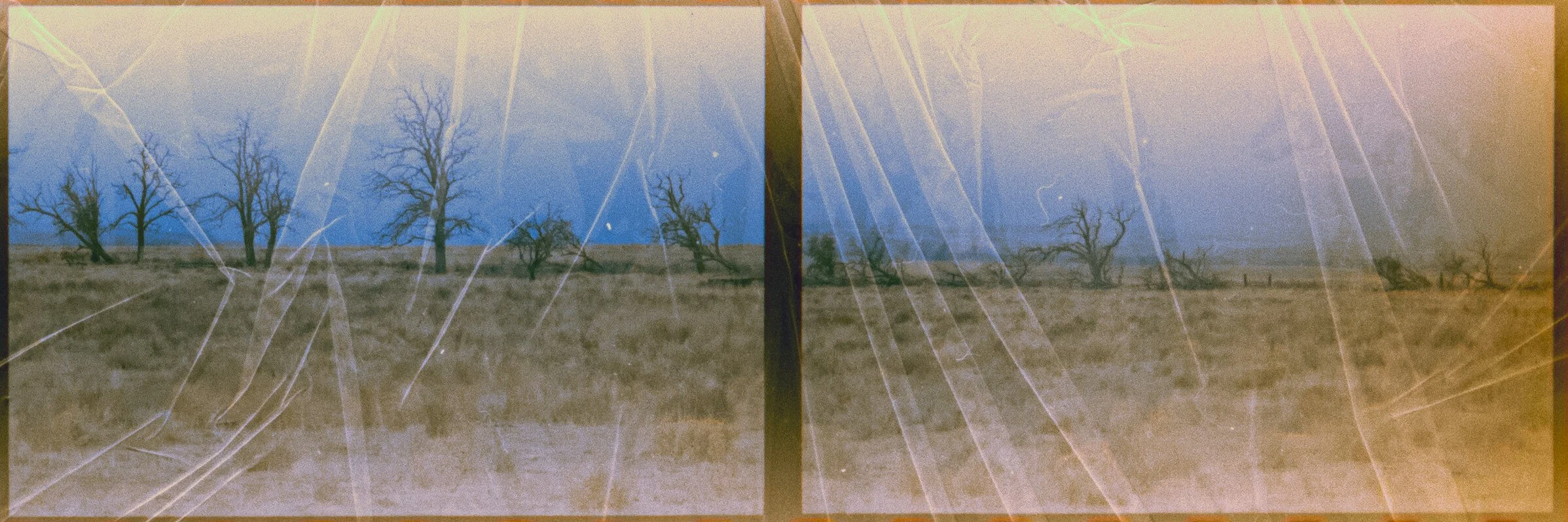

In the novel Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell, the character Agnes has an interaction with her father that forces her to recall a truth about her mother’s death that has been silenced. O’Farrell communicates the emergence of this memory, writing, “It feels to her as though the world has cracked open, like an egg. The sky above her could, at any moment, split and rain down fire and ash upon them all.” The authors in our Fall issue have managed to articulate the quiet, yet sharp return of past relationships, homes, and versions of the self whose presence is invisible yet eternal. The beauty of these stories is in their ability to address how our own memories can feel like a distorted secret we have been asked to forget in order to propel ourselves forward. Collectively, these stories have resonated like the sound of a memory returning: slowly, at first, until a branch breaks, bringing each piece of fruit, each small detail, abruptly within reach.

We hope you will find them as beautiful as we have.

With warmth,

Hannah Newman & Jesse Ewing-Frable

Editors-in-Chief

Sweet Tree Review