peaches and.

by Phoebe O’Brien

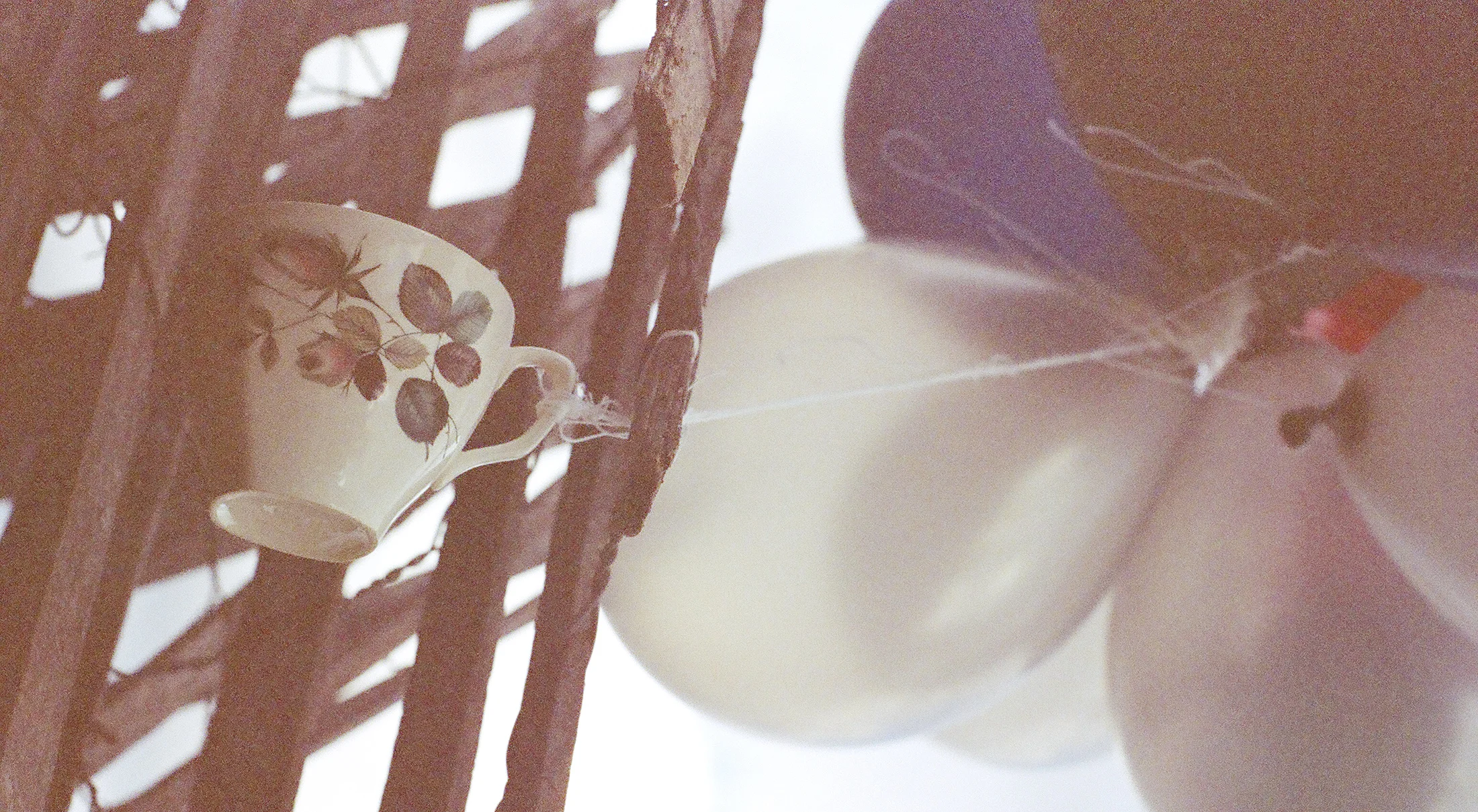

Marble peaches dent the floor and break teeth and have stems of cardboard, leaves of velvet. There were other fruits, too, but none so juicy and cold. None so heavy. The peaches split gratuitous and curvaceous. Some of them were notched so deeply that a wooden pit peeped out and I always tried to reach that; to cobble my fingers through the crack to touch it, but it was always just narrow enough.

I do not believe in God, and I question the person that brought the peaches into being, too. What was the purpose in such falsity? Who spent so much time smoothing marble into peach? Was there nothing better?

The peaches occupied my grandmother’s house for a handful of decades until I unraveled paper and bow one birthday to find them gazing up at me.

“I wanted you to have them,” she said, nails shell pink, earnest and clutched in lap. “They’re alabaster. Real old.”

The impracticality of it all stunned me; I did not have a basket for the fruit that dripped sullen and vivacious on the counter, but the marble peaches had a bowl. I looked at them so long and hard that I swear they paled, as if my gaze scrubbed the dye right out of them.

“Thank you,” I said, hoisting the bowl. “I’ll take good care of them.”

I did. Even when my sheets went sodden and dishes unwashed, I dusted the peaches. Shooed away misguided flies. With the acquisition, my life seemed to become more tactile and exciting: See how this peach is not real! How it glints! You have never seen such a thing!

I couldn’t do anything with them.

The peaches became a pinnacle of disappointment; each day I arrived sweaty and lank from work, and they sat pert. They were stoic through heartbreak. They did not flinch when I smashed a vase or cut my hand making dinner. Their leaves did not droop or wave in the wind. They had never hung from a tree.

Juxtaposition turned obsession and I sat drinking coffee in the mornings, wondering if the peaches’ hardness made life pitifully soft, mortal. Days whirled past and streetlights rose and fell, and the peaches did not move at all. Paranoid, I wondered if I was hardening, too. What a relief to appear pristine, unbothered. Inauthentic.

Much like I could not believe that the peaches were created—it seemed more likely that they had appeared from thin air— I could not believe that there was any way to dismantle them. Yet halfway through a Tuesday, I stood up at work.

“I’m sorry,” I said, coughing my chair back into desk. “I’ve got to go.”

Eyes glazed in my direction; I was not being proper. My cardigan was buttoned wrong, I walked out anyway. Breeze snapped about my ears, my soles drummed the earth, and when I made it home, I swung the door open like epiphany, took to a stone peach with a butter knife.

I was strategic, went straight for the pit. It unhinged with a creak. I found glue. I found a crescent of wood, perfectly angled to fit the gap. I expected it to smell of chemicals, but it only smelled old. Regular and old, just like anything. Like only a thing. A thing someone had bent over, perhaps planted with a tweezer in the slowest, most precise movement. I thumbed it like a prayer, pried a splinter away with my nail.

How very soft it was, how vincible.

I put the pit in my pocket, the peach in the bowl.

Phoebe O’Brien lives in Bellingham as a student, sculptural assistant, and waitress.